An article written by ENIL former volunteer Vy Nguyen

Without the direct and active involvement of disabled experts in the development of new technology, we risk repeating old patterns of exclusion. But true inclusion means more than simply having a seat at the table, it requires participation that is voluntary, well-informed, and genuinely meaningful.

Via a public survey of 32 adults with diverse disabilities across Europe, arecent study by Vy Nguyen at Central European University has shown that the perspectives of disabled people are not just helpful, but essential in the development of new technologies. Their lived experience can provide unique insights into the promises as well as the risks of cutting-edge technologies such as Brain-Computer Interface (BCI).

1. Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) – a future technology for Disabled People?

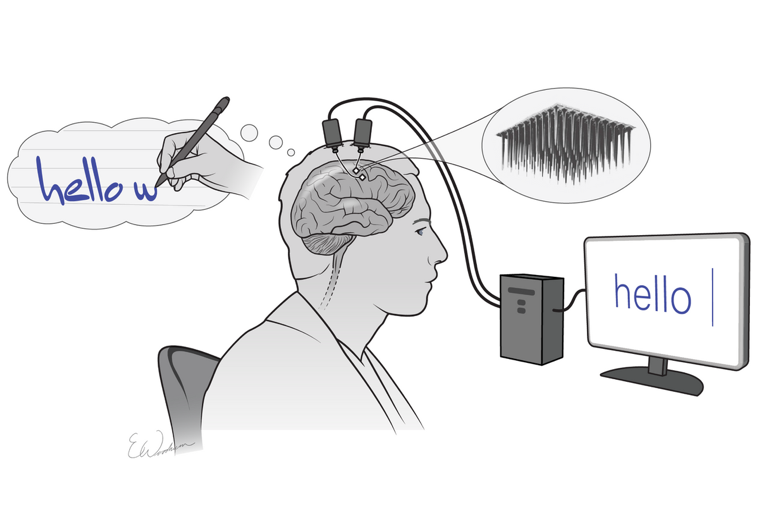

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a device that picks up neural signals and translates them into commands on an external device, such as computers, robotic limbs, or speech synthesizers. For example, BCI users can make the computer write the word “Hello” simply by thinking about the act of typing “Hello”.

Some types of BCI also work wirelessly through a tiny chip implanted on the surface of the brain. Because they require surgery, these are called implantable BCI, or simply brain chips. They offer more precise control than non-invasive devices and are often presented as a promising future assistive tool for disabled people.

Till December 2023, all 67 participants in 28 first-in-human invasive BCI clinical trials were people with motor, sensory, or communicative disabilities caused by spinal cord injuries, brainstem strokes or ASL (Patrick-Krueger, Burkhart, and Contreras-Vidal 2024).

2. How do Disabled People see implantable BCI trials

When presented with a hypothetical BCI trial, almost every respondent in Nguyen’s study (31 out of 32) held some misconceptions about the nature of clinical trials. Many wrongly believed that the trial device would be tailored to their personal needs, or that the trial’s main goal is to directly help its participants.

In reality, clinical trials are designed to test specific technologies and generate scientific knowledge, not to guarantee benefits for their volunteers. Such false expectations are risky because they may lead participants to downplay the potential risks of participating in a clinical trial.

At the same time, the public seems to hold a double-standard view on the use of implantable BCI. A 2024 public survey of over 800 adults in the UK revealed that although nearly 95% of respondents had never used a BCI application, a significant number of them supported the use of BCI for disbaled people. Half of the respondents also felt that it is morally wrong for non-disabled individuals to use invasive BCI, and 65% believed that invasive BCI should be limited to those with physical and/or cognitive disabilities (El-Osta et al. 2025). Another experimental study further shows that the public often blames disabled people who choose not to adopt BCI technology (Sample et al. 2023).

Against this background, it is of utmost importance that disabled people can make informed and autonomous choices when it comes to testing/using emerging technologies. When the 32 respondents were asked what they thought of the opportunity to participate in a BCI clinical trial, there was a strong consensus among respondents that disabled people must retain full autonomy in deciding whether or not to adopt a (trial) technology. Besides divided opinions on the benefits of implantable BCI and concerns about potential trial risks, this emphasis on agency was one of the strongest shared themes in the survey – a key insight that only emerges when we center disability voices.

3. Key Takeaways

In ENIL’s feedback to UNESCO’s ongoing draft Recommendation on the Ethics of Neurotechnology, we have already reiterated the need to mainstream the experiences and interests of disabled across different stages of development. Including disabled people as test-users of new technologies like BCIs is necessary, but it is not enough. Their expertise and experience must also shape the design, ethics, and communication around the trials of these innovations.

To do this:

- Consent procedure must be a more dynamic process. Beyond a mere formality, it should allow participants to share their perspectives on the trials. This also provides researchers with insight into the social barriers their future technologies will encounter. Just as the recent revision to the Declaration of Helsinki has highlighted, there is a need for “meaningful engagement” with the participants and their community throughout the research project (Article 6).

- Transparency in reporting is vital. Researchers and the media must avoid overstating what experimental technology can deliver, so that the general public has a realistic picture of the technology, and disabled people are not pressured into adopting something still in development.