The European Commission is moving ahead with long awaited plans to introduce an EU-wide European Disability Card. To really support the freedom of movement of disabled people, this card must entail full cross-border access to rights and services, including personal assistance.

Florian Sanden, Policy Coordinator, florian.sanden@enil.eu

The European Strategy on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021-2030 announced the creation of a European Disability Card. At the end of November 2022, the European Commission began to move ahead with the plans and published a call for evidence, including an impact assessment and involving the opportunity to give feedback. According to the impact assessment, the European Disability Card “will promote persons with disabilities´ right to free movement and residence across the EU by facilitating the mutual recognition of disability status for card holders within the EU.” ENIL provided input to the call for evidence, containing a detailed statement which can be accessed here.

Barriers to the freedom of movement

ENIL welcomes and supports the plans of introducing an EU-wide European Disability Card. Article 21 of the treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), grants all EU citizens the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States. Disabled are often unable to enjoy the freedom of movement and residence in practice. The fact that disability status are not recognised across borders represents one of the key barriers. A person might be recognised as having one or several disabilities in one member state. If the same person decides to move to another EU country, to take up a job offer or to do an Erasmus+ semester abroad, the disability status does not travel with her or him according to the current legal situation. The new country of residence is under no obligation to accept the disability status granted abroad. For a disability to be recognised, it is necessary to pass the recognition process of the host country. Given that such procedures are often lengthy, in-transparent and require a strong command of the national language, this represents a significant deterrent. For disabled people with support needs or accessibility requirements this can cause an insurmountable obstacle. If a disabled person is a user of personal assistance (PA) and has been recognised as such, this entitlement is not portable. EU countries are at the moment under no obligation to allow a disabled person with an entitlement to PA granted in another member state, access to their national PA schemes. The non-recognition of PA entitlements across borders is closely linked to the non-recognition of disability status. Like-wise without a valid disability status, there is no legal right to reasonable accommodations at work or in education. Financial support in accessing healthcare or assistive devices can not be accessed either. Without full access to rights and services, a disabled person might not able to move to another country.

Automatic access to rights and services for non-disabled people

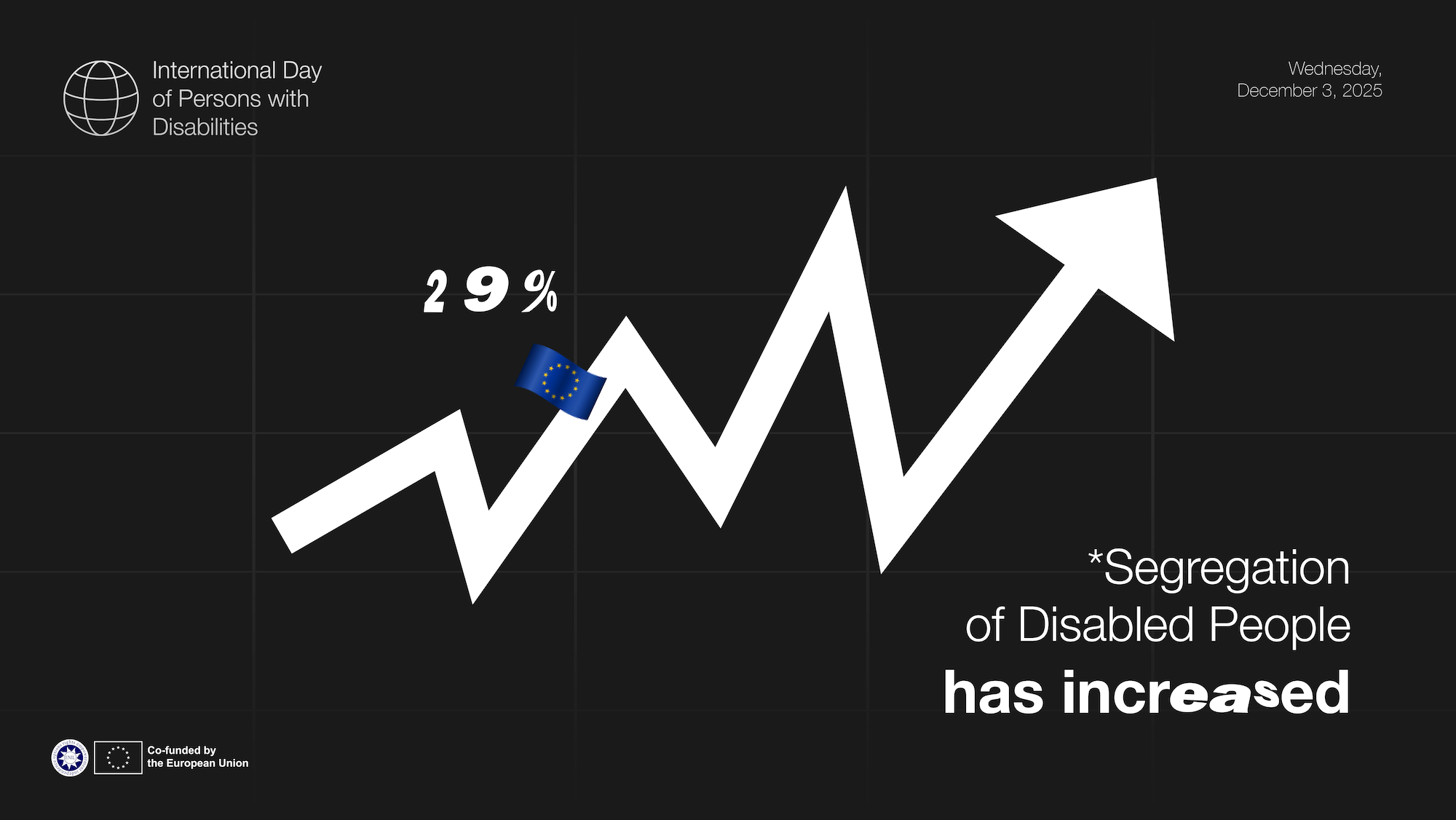

The non-recognition of disability status across borders, including the access to rights and services, is not only problematic because it impedes the freedom of movement for disabled people but also because non-disabled people enjoy considerable support in exercising their freedom of movement. For example, in the area of education EU countries agreed to introduce an automatic, mutual recognition of higher education and upper secondary diplomas until 2025. Already now educational institutions or employers often recognise degrees de facto, enabling full access to rights and services. Regulations 883 and 987 set rules governing the cross-border access to social security systems. A person taking up work in another EU country has to receive the same access to the various branches of the security system as a national from the same country. This implies for example access to unemployment benefits, healthcare and pensions. If a mobile worker, collects pension entitlements in various EU countries throughout the career, those will the summed when the person reaches pension age. The same person is than free to receive to pension in any EU country. When it comes to the automatic recognition of access to rights and services disability is at the moment almost entirely exempt.

National disability cards commonly grant holders preferential access to activities in the areas of leisure, culture, sports and transportation. From 2016 to 2018 the European Commission implemented a European Disability Card pilot project. Eight member states, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Malta, Romania, and Slovenia introduced the European Disability Card as a trial run. In those countries services providers from the areas mentioned, could sign up on a voluntary basis to provide preferential access conditions to holders of the European Disability Card. In 2021 the European Commission published an assessment study. According to the study, users felt that too few services providers participated. Other evidence states that among service providers the European Disability Card remained unknown and was thus no accepted.

ENIL´s position on the European Disability Card

To really resolve the barriers to the freedom of movement, the European Disability Card must not only facilitate but achieve the mutual recognition of disability status between EU member states. A disability status granted in anywhere in the EU must be automatically recognised in the country the disabled person wishes to take up residence. Such a recognition has to imply full access to the rights and services granted to a disabled person who is a national of the country. The full portability of disability status must include the full portability of access to personal assistance. This could work, if either the country of residence accepts access to the national PA-scheme like it is the case for healthcare or if the country that originally granted to PA entitlement pays the direct payments to nationals residing outside its borders, like it is the case for pensions.

Countries are unlikely to accept a foreign disability status if they don´t have faith in each other´s disability recognition procedures. Thus, ENIL advocates for a comprehensive reform and harmonisation of national procedures for the recognition of disabilities and assessments for eligibility for and need of personal assistance. In addition, it is imperative to introduce a common EU-wide definition of disability. Since all EU countries are state parties to the UNCRPD, such a step should not pose a problem.

The recognition of the European Disability Card needs to be legally binding for providers of services in the areas of culture, leisure, sports and transportation to the same degree as recognition of a national disability card is compulsory in a given country. Holders of a European Disability Card must be granted the same preferential access conditions as holders of a nationally granted disability card.

European Parliament and ENIL share position

On December 13 the European Parliament adopted a resolution titled “towards equal rights for disabled people” which supports ENIL´s position on the European Disability Card. In its report the Parliament stresses that “the lack of a common EU definition of disability constitutes a major obstacle to the codification of disability assessment and the mutual recognition of national decision on disability issues”. The resolution urges the European Commission to work on a mutual definition, diagnosis and recognition of disability status. The European Parliament “strongly believes that the EU Disability Card should be based on binding an EU legislative act that should cover a range of different areas beyond culture, leisure and sport”.

Next step

To shape and improve the European Disability Card, ENIL will monitor European Commission´s plans closely and continue to provide input.