By Christos Meletis – ENIL, Volunteer

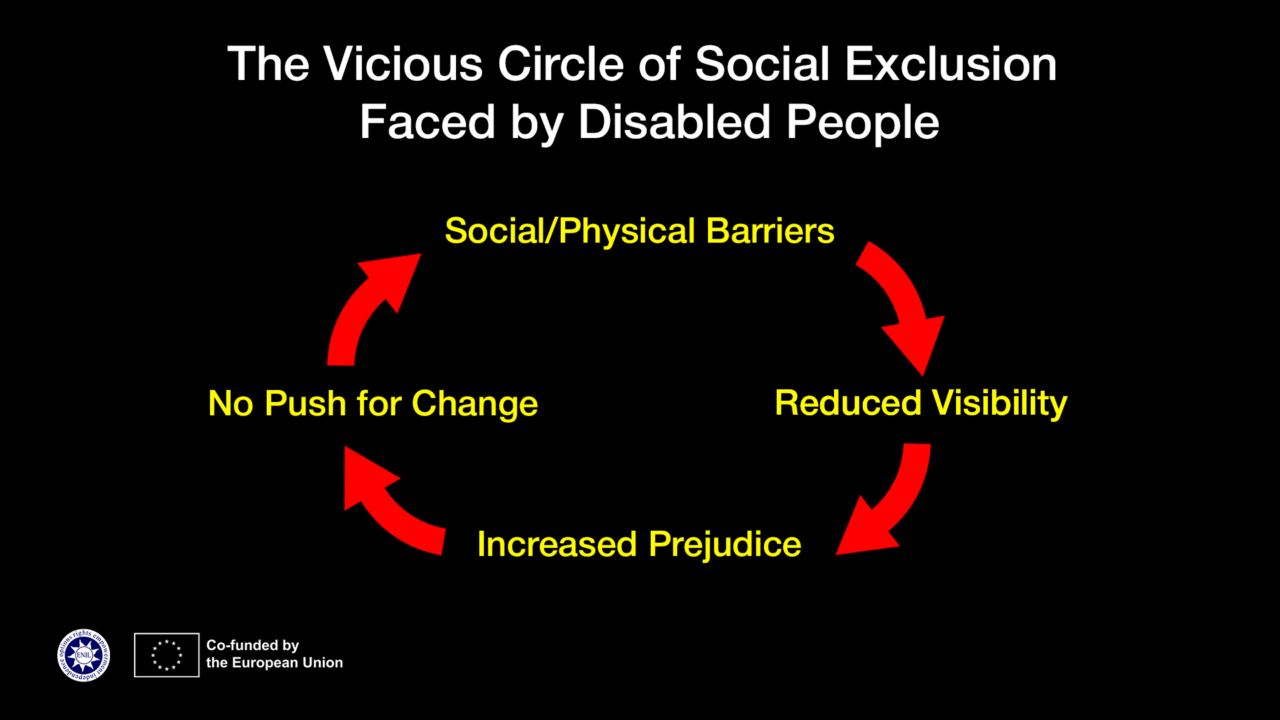

When it comes to the social exclusion of disabled people, there is a powerful negative social mechanism that, if left unchallenged, traps them in a vicious circle of systemic oppression.

On one hand, there are barriers to participation — such as the lack of accessible infrastructure and services — which reduce the visibility of the disability community in society. On the other hand, there is a fear of the unknown among humans, which fuels negative attitudes*. These two conditions reinforce one another, creating a perfect storm of exclusion.

Specifically, many disabled people cannot attend social gatherings or access jobs because of inaccessibility or negative attitudes towards them. They are enrolled in special schools instead of mainstream schools — often due to discriminatory policies — and as a result, non-disabled people rarely have the chance to interact with them in public spaces. When there is little to no interaction with a particular group, it creates fertile ground for prejudice to grow.

This reinforces harmful stereotypes, such as that disabled people are incompetent or constantly grieving their impairments. As a result, non-disabled people may not push for the inclusion of disabled people — bearing in mind, of course, that policymakers and politicians are also people who are affected by the same negative social learning as everyone else.

In short, social barriers lead to reduced visibility, which fuels prejudice, which in turn leads to a lack of pressure for change — further reinforcing those same social barriers and lack of visibility. It truly is a vicious circle. But what is the solution?

In my opinion, this cycle can only be broken by fighting for our rights. We need to stand united and know where to focus our resources to achieve the greatest impact. Changing exclusionary systems is a difficult process, and resistance is to be expected, but with the right actions, a positive domino effect is also possible.

*There is a primal survival mechanism in humans called the ingroup/outgroup distinction, which essentially categorizes people as either “familiar” or “strangers” (us and them). If someone is marked as a “stranger,” we tend to think about them less favorably. Who we perceive as strangers has a lot to do with visible traits, which means this mechanism can influence how we see entire groups — and especially minorities such as disabled people, people of color, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community.