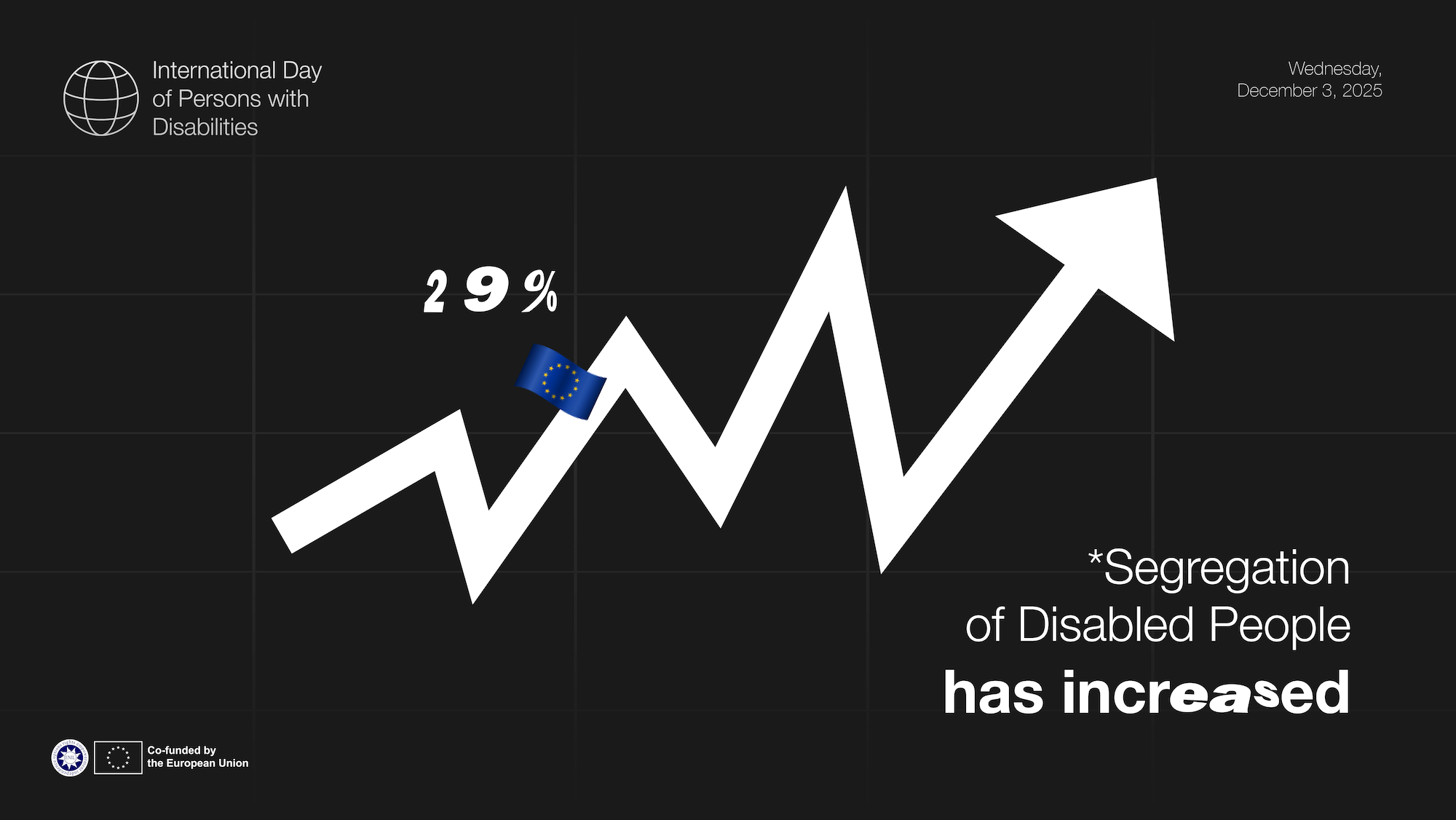

The belated deinstitutionalization in post-communist societies is part of postsocialist care-violence-paternalism, economic scarcity, fear of impoverishment and a transgenerational aversion towards disabled people. In Slovenia alone, more than 22.000 children and adults experience today spatial segregation, loss of choices, and long-term institutionalization.

Taking a look into history, the belated modernization of Eastern European societies after WWII and the socialist policy of gender equality was aimed to solve the “women’s question” through women’s full-time employment, which resulted in part into a profusion of closed and semi-closed institutions for people with different disabilities including mental health issues (Zaviršek 2015) Boarding schools and large long-stay public care institutions were seen as the perfect solution of social protection from the “cradle to the grave,” regardless of a person’s individual needs or abilities.

Paternalistic relationships, control and care for basic material needs were the main priorities of welfare institutions. The residents were neither entitled to any rights nor perceived as persons with their own life trajectory. There was no life beyond staying in confinement. People with the same diagnosis were placed in the same building, and the institution became a collection place for children and adults with different impairments across Slovenia. This consolidated residents’ invisibility and inability to keep contacts with the outside world, the relatives, local community and to live an ordinary life. Encounters with relatives were rare, as the latter often did not have the necessary funding to afford a weekly or monthly visit to the remote place. Therefore, the staff had unlimited power over the residents. Now and then some institutions, like the largest psychiatric hospital Polje in Ljubljana, incarcerated the homeless, “drunkards” and other socialist “lumpenproletariat” to implement the biopolitical “cleaning of the city’s streets.” They were locked in overnight when the highest political delegations with President Josip Broz Tito visited Slovenia (personal communication with one of the directors of the psychiatric clinic, 1992).

After the late 1980s social activists started to question the spatial segregation of disabled persons. New grassroots organizations of disabled persons refused the institutionalization as well as the dominance of the medical model and the old-fashion “invalid organizations’ representatives,” who after 1991 kept their privileged status granted to them during Communist rule. But critical voices were marginalized and instead of deinstitutionalization, new institutions were built. […] Read the full article here.

Written by Dr. Darja Zaviršek, a researcher/activist from Slovenia. The article is reprinted with permission from Gržinić, M., Ivanov, A., Monbaron, J., Stojnić, A. and Rihter, A. (eds) (2018) Tracings Out of Thin Air. Establishing oppositional practices and collaborative communities in art and culture. Ljubljana: Forum of Slavic Cultures.

Find out more about the Independent Living Research Network here.